News Around the World

by Jim Korkis

Disney Historian

Feature Article

This article appeared in the January 15, 2013 Issue #695 of ALL EARS® (ISSN: 1533-0753)

Editor's Note: This story/information was accurate when it was published. Please be sure to confirm all current rates, information and other details before planning your trip.

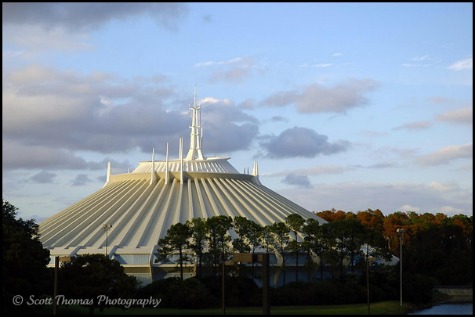

(EDITOR'S NOTE: On this day in 1975, January 15, Space Mountain opened in Walt Disney World. Happy 38th Anniversary, Space Mountain!)

The Magic Kingdom in Florida was never meant to be a clone of Disneyland. From the very beginning, the plans were to have some attractions and experiences that were only available at the new park to encourage potential guests to want to visit both parks. After all, why would West Coast guests want to plan a vacation in Florida just to see the same things they could enjoy more easily in their own back yard?

The Magic Kingdom in Florida was never meant to be a clone of Disneyland. From the very beginning, the plans were to have some attractions and experiences that were only available at the new park to encourage potential guests to want to visit both parks. After all, why would West Coast guests want to plan a vacation in Florida just to see the same things they could enjoy more easily in their own back yard?

However, The Walt Disney Co. soon discovered that East Coast audiences, only a small fraction of whom had ever traveled to Disneyland, wanted some of the classic attractions associated with the West Coast theme park.

Some amazing ride concepts like Disney Imagineer Marc Davis' Western River Expedition were put on the shelf so that the more famous Pirates of the Caribbean could take up residence in Orlando. Yet, when the Magic Kingdom opened in 1971, there were some Florida-only attractions from the Mickey Mouse Revue to the Country Bear Jamboree. For the proposed Phase Two of the Florida Project to premiere by 1975, other Florida-only projects were announced, including the iconic Space Mountain.

While Disney Imagineer Marty Sklar autographed my copy of the original hardcover Disneyland souvenir guide that he wrote in 1964, I asked him what was one of his most difficult projects over the decades. I was surprised that he admitted it was Space Mountain.

"Most difficult project? Trying to sell RCA, which was willing to put up $10 million for an attraction," said Marty with a smile. "John Hench and I designed a ride to go inside a computer. We pitched it to all the lower folks and finally had to make the pitch to Sarnoff [David Sarnoff, general manager of RCA]. We put up the storyboards and we were told that Sarnoff always sat at the head of the table. So he could barely hear us and couldn't see the small storyboard drawings. He wrote a note, and passed it to his vice president who passed it to a subordinate, etc. so it eventually got to me. The note read 'Who are these people?'

"Nobody had told him why we were there or what we were doing. Defeated, I told Hench to come up with a project he wanted to do and then we would try to sell RCA on it. So Hench came up with Space Mountain. When it came time to pitch, I insisted that Card Walker and Don Tatum accompany us, since Sarnoff knew them. Also we insisted that Sarnoff sit in the middle of the table.

"The RCA people said 'no' and I said, 'We are talking to the person sitting in that chair.' So they put a person guarding the chair and when Sarnoff came in they said, 'The Disney people would like you to sit here.' Sarnoff said, 'Sure.' Nobody had ever asked him before to sit anywhere else. They just assumed he wanted to sit at the head of the table. We sold the Space Mountain project."

Actually, the birth of Space Mountain began much earlier in a series of meetings with Walt Disney in 1964. A design team headed by Hench came up with a concept of redeveloping Tomorrowland in Disneyland with a Space Port that would feature a steel track roller coaster with four separate tracks twisting and turning around each other in a serpentine fashion to mimic space flight.

It was Walt who wanted the roller coaster to be in the dark so he could have precise control of the lighting and to project images on the interior walls. For the tunnel of his backyard miniature railroad, the Carolwood Pacific, Walt had insisted on an "S" curve in the tunnel so that guests entering could not see the light at the end and so had no way of knowing how long it was or how to acclimate themselves to where they were.

Hench came up with the original drawing for the exterior of the attraction in 1965, and it is very similar to the final cone-shaped version familiar to park-goers today. That artwork appeared in the 1965 Disneyland Pictorial Souvenir Guide sold in the park. However, for a variety of reasons, Space Mountain was shelved and did not debut with the new Tomorrowland in Disneyland in 1967.

It wasn't until that meeting with RCA that the project was revived for the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World. Imagineers used computers (a rarity in the 1970s) to design the two twisting and crisscrossing guide paths so that each curve and bend contributed to a smooth but exhilarating "flight" — the first computer-controlled roller coaster ride system.

As early as 1972, RCA sent out a publicity release featuring an "artist's conception" that refers to the ride as "the thrilling Space Voyage in Tomorrowland opening in 1974."

According to Disney publicity from 1975, the storyline of the attraction was that "Space Mountain captures the essence of Superspace. The expectant 'space voyager' is transported through the space station launch portal, and through the vast man-made 'solar field.' He then orbits the glowing 'satellite,' becomes engulfed in spectacular nebulae and plunges past myriads of strange stars and unknown galaxies to begin re-entry."

The Walt Disney Co. proudly proclaimed that the attraction took full advantage of knowledge gained during the manned and unmanned space probes conducted by NASA. Former astronaut Gordon Cooper, commander of Mercury 9 and Gemini 5, became a member of the Disney team and provided personal consultation to help ensure the authenticity of Space Mountain. He saw Space Mountain as "an attempt to give people the most realistic feeling of what they might encounter in space without actually taking a real space flight. As we gain new knowledge and insight concerning space, Space Mountain will be improved upon in true Disney fashion."

It was the first indoor roller coaster where riders were in total darkness for the length of the ride so they couldn't tell where the drops or turns would occur. It was also the first thrill ride that was controlled by computers to maintain safety. Space Mountain was controlled by a pair of very sensitive Nova 2/10 computers, which were able to respond instantaneously to any unexpected event by immediately halting all mechanical movement.

Each vehicle was made up of two six-passenger "rocket sleds" in tandem that were separated by a "block zone," a part of the track which consists of mechanisms to slow or stop the vehicle in case of an emergency situation. If the vehicles were too close together at any point on the track, the computers would stop all vehicles from that point back to the loading area until an adjustment could be made.

Dave Snyder, manager of scientific programming at the time, stated that the computers must be taught to watch each of the 11 or 12 vehicles on the spaghetti-like complex of track and to time each one. When faced with incoming data, a computer must make one of three decisions concerning operation of the attraction: to halt everything, to inform the ride operator of a possible impending problem or to allow the system to proceed as normal. If there were even a remote likelihood of vehicles colliding, the entire system would shut down automatically. If the computers suspected that some aspect of the attraction was malfunctioning, a light flashed the possible trouble on a status board inside the control booth.

While this type of system is fairly commonplace today, in 1975 it was highly innovative and emphasized Disney's concern about guest safety. There was a movie in which Gordon Cooper explained what was to happen and even a "chicken" escape ramp for those guests who might then decide that perhaps this is not exactly the attraction for them.

In the pre-show area were space frame portals to provide a view of the attraction in actual operation. In effect, every effort was made to make the guests comfortable. Even the track was designed so that passengers would experience the least degree of physical disturbance during their ride.

"Since each vehicle runs at an approximate speed of 40 feet per second [about 28 to 30 miles per hour], smooth transit is essential," claimed Disney publicity in 1975.

In the event of a power failure, an emergency backup system called an Uninterruptible Power Supply provided power to the computer system. This emergency energy supply lasted for about 30 to 45 minutes — more than enough time to activate emergency systems and to return all vehicles to the unloading area.

Hench insisted on observing the first guests to take the trip. At the end of the ride, the guests were dead silent. "Some seemed to be hyperventilating," Hench remembered. "One woman stirred first and got out of the car. She knelt down and loudly kissed the carpet. I followed them about halfway up the ramp. They broke into spontaneous laughter… these people had not felt so alive in years."

On January 15, 1975, Space Mountain's first official mission was led by Colonel James Irwin, pilot of the Lunar Module on the Apollo XV mission to the moon.

"Just as Walt had wanted," Hench later recalled, "we made most of the ride's structure invisible to guests, thanks to pinpoint light projectors, which do not reveal forms. Being inside Space Mountain is like orbiting in space. [The attraction] is full of surprises. Guests can't see where or when the next turn or dive is."

According to Hench, "Space Mountain has an abstract, contemporary form and tells its story architecturally." Describing the attraction as "above all an experience of speed, enhanced by the controlled lighting and projected moving images," Hench observed, "it evokes such ideas as the mystery of outer space, the excitement of setting out on a journey, and the thrill of the unknown."

Considered one of the primary artisans behind Space Mountain, Hench was involved in the creation of a total of five versions of Space Mountain for Disney theme parks around the world.

Space Mountain has undergone many renovations over the years, but it remains one of the original highlights of the Magic Kindgom at Walt Disney World.

===============

RELATED LINKS

===============

Other features from the Walt Disney World Chronicles series by Jim Korkis can be found in the AllEars® Archives:

http://allears.net/ae/archives.htm

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected Disney Historian who has written hundreds of articles about all things Disney for more than three decades. As a former Walt Disney World cast member, his skills and historical knowledge were utilized by Disney Entertainment, Imagineering, Disney Design Group, Yellow Shoes Marketing, Disney Cruise Line, Disney Feature Animation Florida, Disney Institute, WDW Travel Company, Disney Vacation Club and many other departments.

He is the author of two new books, available in both paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon.com:

— "Who's Afraid of the Song of the South"

— "The REVISED Vault of Walt": Paperback Version / Kindle version

-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-

Editor's Note: This story/information was accurate when it was published. Please be sure to confirm all current rates, information and other details before planning your trip.