This series of blogs deals with the Walt Disney Company’s participation in the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, a watershed moment in the entertainment giant’s history. This installment focuses on General Electric’s Progressland, featuring the Carousel of Progress.

- LOCATION: Industrial area.

- SPONSOR: General Electric.

- MAIN ATTRACTION: Carousel of Progress.

- RIDE SYSTEM: Rotating theater seats with four fixed stages.

- CAST: 32 Audio-Animatronics “actors.”

- OTHER SHOWS: The Skydome Spectacular; Nuclear Fusion Demonstration; Medallion City.

- NOTEWORTHY SONG: “There’s a Great, Big Beautiful Tomorrow,” by Richard and Robert Sherman.

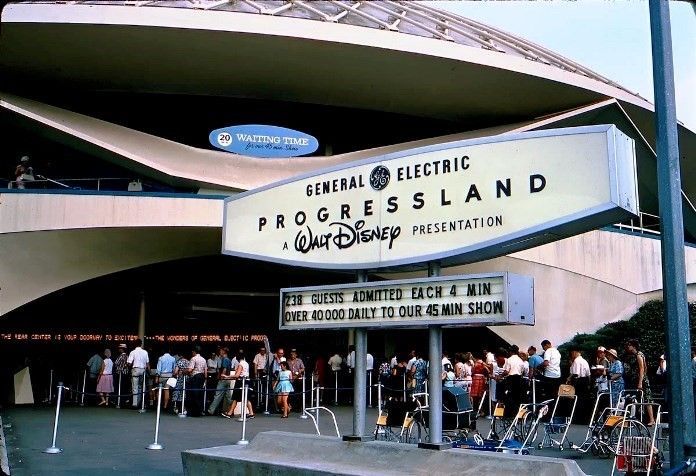

More than any of the other Disney-created New York World’s Fair pavilions, General Electric’s Progressland – which showed guests how the world of electricity had grown in leaps and bounds over the years – was all about change.

And those changes occurred both inside and outside the massive domed building, designed by the firm owned by Walt Disney’s good friend, Welton Becket.

A partnership between Disney and General Electric for an attraction was first proposed in the late 1950s for Disneyland. Edison Square was to show folks “an astounding dramatization” called Harnessing the Lightning. The new attraction was so far along in planning that it was featured as a “coming attraction” in Disneyland guide maps.

But GE switched gears and decided to drop Edison Square and turn its attention to sponsoring a pavilion at the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. Naturally, Disney was asked to lend its expertise to the new project.

The pavilion featured an eclectic mix of shows and displays. There was The Skydome Spectacular, which took advantage of the pavilion’s concave ceiling to provide “a dazzling sequence of thunder, lightning, solar flares and spinning atoms.”

And there was Medallion City, a product display area touting GE’s latest advancements for the home. Tucked in Medallion City was The Toucan and Parrot Electric Utility Show, which was written by Marty Sklar … much to his chagrin.

“Oh, god, I hated it,” he said bluntly. The show featured two Audio-Animatronics birds [one was hypnotized and thought he was actually back at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair] chatting with an animated utility pole transformer about – you guessed it – electricity. ‘Nuf said.

But by far the most talked-about show under the Progressland dome was the Carousel of Progress. The attraction followed four generations of a typical American family as they traveled through the various stages of electrical advances in the home, from the late 19th century to “modern” times in the mid-1960s.

One of the most important aspects of the show was the theme song, composed by Disney Studios songwriters Dick and Bob Sherman. “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow” not only served as the anchor of the Carousel show, but the song epitomized the optimistic spirit Walt Disney embodied.

The Shermans’ tune was arranged by Buddy Baker to reflect the various eras that were represented during the attraction – the 1890s, the 1920s, the 1940s, and, finally, the swingin’ 1960s.

The script had to be rewritten slightly after the dogs were added – giving GE a plug in the process – with Allen at one point admonishing his growling pooch. “Now stop that! He [meaning the audience] may be a good customer of GE.”

The dogs’ names during the show? Rover, Buster, and Sport.

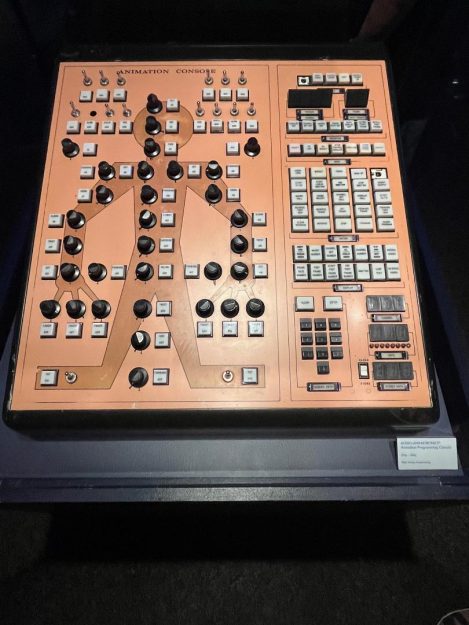

The 32 Audio-Animatronics figures used in the Carousel show were the most “human” figures ever used in one attraction at the time. It was quite a challenge for Disney’s creative staff, with a technology they were just beginning to master.

The carousel stages also employed a classic theater technique called “scrims.” Smaller rotating stages to the left and right of the main stage were concealed by a thin curtain; when the lighting was lowered on the main stage and was turned up behind the curtain, the audience could see what was behind the previously hidden corner stages.

It allowed for several different scenes to be played out by family members of each era, like the mother, children, grandparents, and a clever house guest named Orville who created “air cooling” with a fan and a block of ice.

Gurr played a key role in bringing the figures to life by devising a standardized parts system, allowing the figures to be mass-produced.

“We came very quickly to learn how we could … do animated figures in a wholesale method,” Gurr said. “I started a whole system of parts numbering, how we could do the engineering, drawing, and working with the shops.”

The figures were linked to a computer system that, by today’s standards, was quite primitive. Yet, the entire presentation – seats rotating around fixed stages, dozens of Audio-Animatronics figures, lighting, and audio – worked seamlessly.

During the winter of 1964-1965, Disney addressed a problem that had arisen outside the Progressland pavilion during the opening season. It seems the planners didn’t figure on so many people visiting the attraction, and long lines often backed up outside the entrance and snaked haphazardly in and around the Fair’s Industrial Area.

A covered waiting area was erected between seasons, which kept guests out of the sun during the summer months. The now-familiar switchback lines also were installed to keep things far more orderly.

Sklar also remembers that the Progressland pavilion became the first Disney attraction to use a wait time sign, which gave guests an idea of how long the wait would be; similar signs are now employed at the entrances of just about every Disney attraction worldwide.

The Carousel of Progress figures and sets were transported back to California after the Fair closed. They were reassembled and opened in a circular theater in Disneyland in 1967. The show debuted in Walt Disney World in 1975, where it still plays to appreciative audiences to this day.

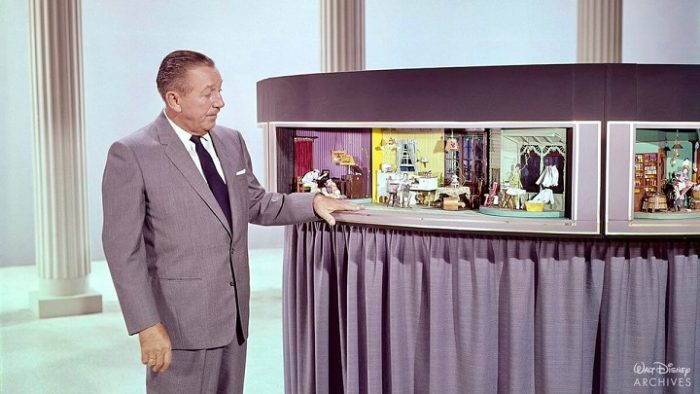

After guests experienced the Carousel of Progress at the Fair, they could take a look at Walt Disney’s vision of the future.

“You went into the General Electric exhibit and there were a whole bunch of things there regarding community development,” Sklar said.

“What Walt had decided was that we should do a model of this concept called EPCOT, and we built this big model that was upstairs on the second floor in the Carousel pavilion. That model fascinated Disneyland guests for five years.

“It was basically a depiction of the EPCOT community that is represented in Walt’s EPCOT Film.”

Part of that model can be seen today along the PeopleMover route in Tomorrowland at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World.

Fourth in a five-part series. Next time: Ford Motor Company’s Magic Skyway.

Chuck Schmidt is an award-winning journalist and retired Disney cast member who has covered all things Disney since 1984 in both print and on-line. He has authored or co-authored seven books on Disney, including his On the Disney Beat and The Beat Goes On for Theme Park Press. He also has written a regular blog for AllEars.Net, called Still Goofy About Disney, since 2015.

Trending Now

Looking for this popular Disney LEGO set? You can now find it at Costco!

Something brand new is coming to Universal Orlando and we've got the details!

Universal just announced the opening date for the new DreamWorks land!

Disney has brought their theme parks into Disney+ in a whole new way.

Tomorrow, April 29th marks a big day for Universal Orlando fanatics, as they make a...

We bet we'll be seeing a LOT of people in these new Amazon shirts in...

We found the next t-shirt for the EPCOT-loving Disney dad in your life!

The Bay Lake Tower is about embark upon a massive refurbishment.

We've got some bad news about a popular Disneyland ride.

While several attractions around Disney World will remain closed this week, one closed restaurant is...

We bet you didn't know about this Disney Springs discount!

Check out aerial photos that show the latest construction progress on Universal's new hotel featuring...

Disney World is experiencing some low crowds right now!

We found your perfect Hollywood Studios tee.

We apologize for ruining your day in advance, but if we have to know these...

We dined at one of the most exclusive spots in Disney World, and we've got...

You can enter to win a FREE Disney Loungefly for a limited time!

A low-cost airline has paused one of its direct routes to Orlando, Florida.

We're reviewing 9 new eats from the 2024 Pixar Fest at Disneyland Resort!

We've got a WARNING about Hollywood Studios one day this summer!